Article from Municipal Sewer & Water Magazine (link)

Squeezing Water From Waste

With few discharge options, desert district sets a new standard for reuse

August 2019

By

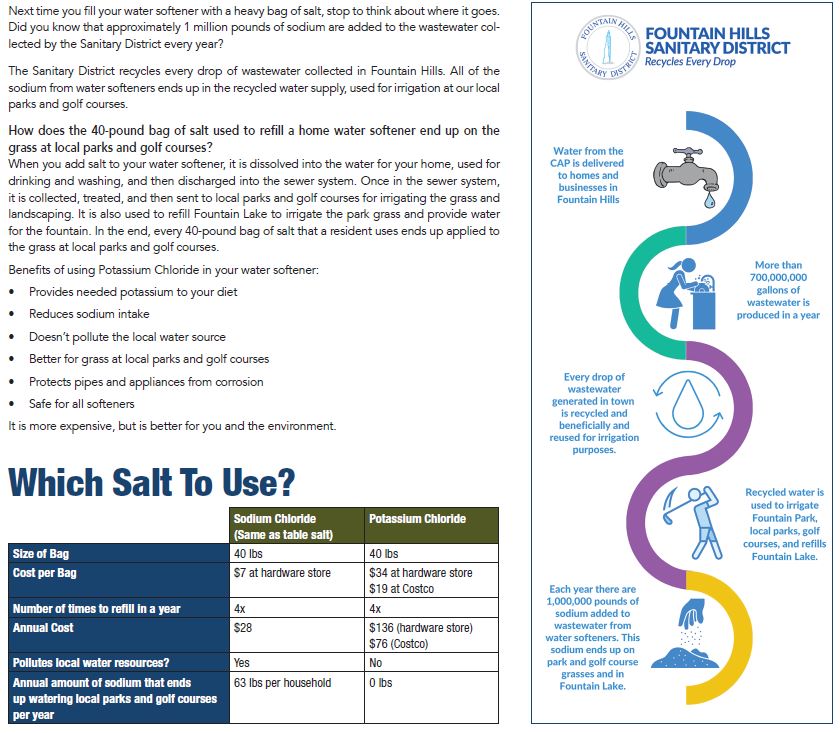

Fountain Hills Sanitary District deserves all the credit for reusing “every drop” of wastewater it collects from its 15,000 sewer connections. A 100% reuse standard is admirable and praiseworthy, but the Arizona district had little choice in the matter.

The community of Fountain Hills is a greater Phoenix area desert community blessed with hilly topography — mountains and canyons — and picturesque flora. Combined with 12 months of dependable sunshine, the desert setting attracted 20th-century snowbirds and other denizens of the north. They flocked here as modern-day Yavapai, the Native American “people of the sun” who originally occupied the area.

As the population increased, however, so did pressure for efficient and sanitary disposal of treated wastewater. This is where things got interesting because the sanitary district was hemmed in, both laterally and vertically, by jurisdictional and physical barriers.

“We are different from other communities,” explains Dana Trompke, district manager. “Most have a discharge permit and can dispose of treated effluent into a river. We don’t have that option. We tried to get a discharge permit approved earlier, but the effort failed because we have two Native American communities downstream from us, hydrologically and geologically. Our treated water would run out of our jurisdictional boundaries and affect the tribal lands.”

With the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation and Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community thus situated to bar simple discharge of treated water into the Verde River, a natural alternative was to introduce treated water into the underlying aquifer via recharging ponds. This entails creating earthen bowls to pond treated water, which then slowly percolates downward through underlying soil into water-bearing strata far underground.

Turns out, Fountain Hills doesn’t have that option either. “That works when the underlying soil is sandy or some other permeable material,” Trompke says. “We are underlined with rock, so we can’t recharge. It just won’t perc. If I had acres suitable for recharge, we would be doing that.”

The sanitary district’s solution to this disposal challenge evolved through the years as the community’s population increased. Its 100% recycling effort essentially began in 1974 when it started disposing of treated effluent into a man-made lake. The 33-acre body of water is the signature feature of the community because 12 hours a day a fountain in its center periodically shoots water up to 560 feet into the air — a display once ranked as the highest fountain in the world. The sanitary district kept the 100-million-gallon lake full by piping effluent directly to it from the district’s wastewater treatment plant, a plant that today can convert up to 2.9 mgd of wastewater into top-rated Class A+ recycled water.

Unfortunately, this disposal solution proved inadequate as the community grew and the volume of recycled water exceeded the lake’s capacity. At that point, the sanitary district sent surplus effluent from the treatment plant to vacant areas of Fountain Hills to spray-irrigate natural desert grasses. That disposal method also proved short-term as the green spaces eventually became developed housing sites, which meant they no longer were acceptable disposal grounds. Today, besides running into the lake, treated water flows to irrigation systems for community parkland and public and private golf courses.

Managing supply

Customers of the Fountain Hills Sanitary District are 98% residential. While this is a comfortable constituency in terms of collection, it doesn’t offer the district many potential commercial customers for its recycled water. There are zero industrial washing or rinsing operations that need extra water, for example. “We just don’t have any industry that would benefit from it. There’s not large enough consumption to be worth the effort,” Trompke says.

The rest of the effluent-handling story is about seasons. Caring for putting greens in desert summers requires three times more irrigation water than in winter. However, the sanitary district’s treatment plant doesn’t produce three times more effluent in the summer.

“Our reclaimed water demand far exceeds the supply in the summer and supply far exceeds demand in the winter,” Trompke says. A way to balance the fluctuation in supply and demand had to be found. The solution came in 2001 when the district drilled and equipped five aquifer storage and recovery wells to harbor oversupply underground until it is needed, at which point it is pulled to the surface again.

“When we are making more treated water than the golf courses and parks are using, it’s recharged into the wells. We currently store up to 300 million gallons of highly-treated recycled water in the winters for use in summer months. Our wells have been successfully operating for 19 years, which may be the longest any aquifer storage and recovery wells have been operating in Arizona.”

The put-and-take storage system includes monitoring wells on the downward gradient of the subterranean storage area to make sure the treated water doesn’t migrate away and into adjacent water systems.

Above and beyond

Dumping water underground for future use might sound simpler than it is. “There is a lot of maintenance,” Trompke says, beginning with the system’s “advanced water treatment facility.”

When the wells were sunk, the district upgraded its treatment regime to include microfiltration, thereby ensuring the treated water wouldn’t negatively impact the aquifer. The facility has since added a Tonka Water brand Ultra Filtration system using DOW 0.03-micron membranes and a WEDECO – a Xylem Brand – ultraviolet light disinfection system.

“The district went way above and beyond any required standard when it introduced the water in 2001, and the plant has since been upgraded. We are pretty confident we have done what we can to protect the aquifer and extend the life of the wells,” Trompke says.

Making it work

All this industrious — if not industrial — use of effluent is the feather in the cap of the sanitary district, and it begins with 211 miles of collection lines, most of which consists of 8-inch-diameter pipe with some 24- and 30-inch collectors in the mix. Distribution lines running from the plant total 15 miles and range up to 18 inches in diameter.

The hilly terrain is a double-edged sword for the district. “We have beautiful views and beautiful building lots, but it can make it difficult to pump the sewage,” Trompke says. Consequently, the district has 19 lift stations — the oldest installed 30 years ago and the newest about a decade ago. Most of the system pipe was put in the ground less than 40 years ago.

“Relative to other parts of the country, we don’t have an old system,” Trompke says. Consequently, pipe replacement at this point is occurring routinely, but not urgently. A half mile a year of cured-in-place relining of collection lines is budgeted for the next three years, the work going to contractors. “Our staff is really good at sewer line repairs and we have done manhole rehabilitation, but it is more economical to sub out the CIPP work.”

While the district doesn’t have its own relining equipment, the yard does include a Vac•Con combination jet/vac truck, dump and pumper trucks, a camera truck for RapidView IBAK North America robotic camera inspection work, a couple of backhoes, forklifts and so on. “We are big enough to have one of everything.”

Trompke is more effusive in talking about the district’s 43 employees, most of whom are maintaining lines, plant and equipment. “We have a fabulous maintenance team,” she says. “They treat the equipment like it’s their own. I don’t know how many times I’ve heard them say, ‘I treat it like it’s my own.’ They have been phenomenal. I give them lots of credit.” This sense of ownership may be behind the stability of the staff, which counts numerous members who have been on the job for 25 years.

Capitalizing

The sanitary district’s sewer rates are just as stable as its staff. Fountain Hills charges customers $28 a month for sewer service. An in-house review of area rates 18 months ago showed Fountain Hills rates to be “right in line” with neighboring systems. One reason the district is debt-free and not raising rates despite upgrades and build-outs is because it has two streams of revenue — customer fees and tax income. As a stand-alone district, it has taxing authority, the income from which it generally uses for capital projects.

The current large capital project is replacement of the pump and pump controls at two of its five aquifer storage and recovery wells. The units in the park adjacent to the lake are in subsurface metal vaults. Leakage from irrigation is rusting and corroding the vaults. The new systems will be relocated to ground level in dual-purpose buildings that will also contain public restrooms. The twin projects should be complete by year’s end.

Most recently, the district replaced inefficient, 20-year-old, 40 hp centrifuges at its main treatment plant — installing 3 hp and 5 hp HUBER Technology disc thickeners and screw presses in the solids digesting and dewatering stage of treatment. The upgrade is expected to reap a 15% savings in electricity costs.

Fountain Hills Sanitary District doesn’t actually recycle every drop, as it sloganizes, of course. No human activity of this scale is that efficient. But it does reuse virtually all of the sewer water it collects, which is no small feat. Some 15% of treated water is utilized in-house — in influent screening spray water and backwashing filters and the like. Trompke says the other 85% of the untreated wastewater “that comes in the door, we actually deliver back out to customers” as treated effluent. That’s the stuff irrigating grasses and plants in parks and on golf courses and spouting gaily from the famous fountain to give the desert community part of its vibe.

Getting the word out

Sewer treatment and distribution of effluent is not what most people think of upon arising each day. All the necessary technical, administrative and maintenance labor in sewer work generally is out of sight and out of mind. This can be a problem for any agency needing community support.

Fountain Hills (Arizona) Sanitary District is no exception. “I think Fountain Hills, like a lot of communities, operated for the last 10 or 20 years with the philosophy of doing the work without being heard, seen or smelled,” says Dana Trompke, district manager. She has been in the manager’s chair for two years now and brought to the district a different philosophy.

“One of my initiatives is to improve our community education and communications so that our customers do understand that extensive efforts are being made to protect this area’s water, and that we play a vital role in it.” To that end, Trompke tasked Cathy Eberhardt, assistant administrative service manager, to also serve as communication and education officer.

Trompke says the outreach will build on the district’s “already excellent reputation in the community. Anytime we have a sewer backup in a home or something, we go above and beyond to correct the situation. We get a lot of appreciation expressed for our attentiveness and quick response.”

Still, the manager isn’t sure the average customer appreciates how efficiently and thoroughly the district is reusing treated wastewater to irrigate public grounds and top off Fountain Lake: hence a revamped district website and more systematic communication from the central office.

The linking of the district to its customers will continue as the population of the 12,000-acre district continues to grow, as it steadily is. The desert community experienced peak growth in the 1990s, but new developments are springing up again. The development is ratcheting up demand on the district because the new units are being populated more densely — which translates into more wastewater.

“What we are seeing is that developers are changing the product they deliver,” Trompke says. “Everything coming right now is high-density, multiple-family construction. The area was originally planned for mostly single-family homes, so that will be a challenge for us. We are doing the master planning right now and identifying what we need to do to prepare for more dense development. Not all of our infrastructure is built out yet, but we’re making sure we will be set up to take care of the district’s needs.”

Desert challenges and rewards

Living and working in a desert community offers challenges and satisfactions to wastewater agencies like Fountain Hills Sanitary District. The southern Arizona district has turned a liability — a growing volume of wastewater with minimal options for disposal — into an asset benefiting the community and the district.

“I think every area has its unique challenges,” says Dana Trompke, district manager. “Too little water, too much water, wildfires — every region has its challenges. The fact we don’t have a river discharge permit has pushed us to a level of sophistication and advancement that other facilities didn’t have to reach. Out of necessity, we went far beyond where we would have otherwise. It was challenging and also exciting and rewarding.”

The challenges aren’t going away in a hot, dry region where comfort isn’t achieved without effort. The area receives about 10 inches of rain a year “and it comes on two different days,” Trompke says only half facetiously about the area’s occasional inundation in monsoon or residual hurricane rainstorms. At the other extreme, the state is a half-dozen years into a drought.

Naturally, such conditions tend to concentrate thoughts on weather — and on climate change. “We do talk about climate change,” the manager says. “In our planning, we weigh what our long-term supply of water is going to be and how we will be able to manage it. It will require planning, resiliency and redundancy. It will be challenging, but we are up for it.”

While the district recycles most of its wastewater for irrigation, ultra-refinement for potable purposes isn’t an option. “For Fountain Hills Sanitary District, our legal authority is only collecting, treating and disposing of sewer water. In Arizona, it currently is illegal to convert sewer water to drinking water. The state is reviewing that policy to determine under what conditions it would allow that. But as of this moment, we don’t have the legal authority to do it.”